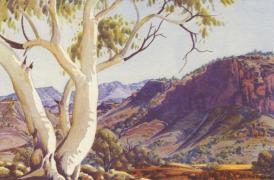

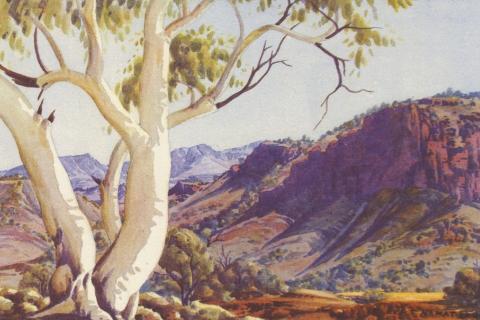

The country of the Western Arrarnta was bought to life in vibrant shades when painted by Albert (Elea) Namatjira (1902–1959), and other artists of the watercolour school of Hermannsburg. Common subjects in their paintings are the distant mountains and gorges, the river systems, white- trunked gum trees, rocky valleys and the creeks. The area is one of the best watered parts of Central Australia with pale-yellow sands of the wide river beds, the smooth white trunks of the eucalypts and their pale green leaves contrast with the orange hues of the rocky ranges, all combine to provide endless inspiration for the artist’s soul.

Albert (Elea) Namatjira was born on 28 July 1902 at Hermannsburg (Ntaria) to Namatjira (later baptised as Jonathan) and his wife Ljukuta (Emilie). In 1905, he was baptised into the Lutheran church along with his father. He attended the school at Hermannsburg Mission and lived in the boys’ dormitorywith other boys which is located at the western end of the historic precinct. At the age of 13 he spent six months in the bush and underwent initiation.

He left the mission again at the age of 18 and married Ilkalita, a Kukatja woman. Eight of their children were to survive infancy: five sons (Enos, Oscar, Ewald, Keith and Maurice) and three daughters (Maisie, Hazel and Martha). The family returned to Hermannsburg in 1923, where Ilkalita was baptised as Rubina. In his boyhood, Albert sketched ‘scenes and incidents around him …the cattle-yard, the stockmen with their horses and the hunters after game. He later made artefacts such as boomerangs and woomeras.

Encouraged by the mission authorities, he began to produce mulga-wood plaques with poker-worked designs. In 1932, he was commissioned by Constable W. MacKinnon to make a dozen oval mulga plaques featuring his camel patrol. Meanwhile, he worked as a blacksmith, carpenter, stockman and cameleer-at the mission for rations and on neighbouring stations for wages.

In 1932, and again in 1934, the artists, Rex Battarbee and John Gardner, visited Hermannsburg on painting trips. Diary entries of both men speak of ‘a young aboriginal man visiting their camp on a number of occasions, showing great interest in what they were doing’.

During the 1934 visit, the two men held an exhibition of their artwork in the schoolhouse. Their paintings of the country that the local Arrarnta knew so well, attracted great interest and it was noted that Albert returned several times to gaze at the watercolour landscapes on display. Albert asked missionary Albrecht for some paper, paints and brushes but his request was not initially taken seriously. After persistent requests, Albrecht and Battarbee agreed that on Battarbee’s next visit Albert would receive his equipment and lessons.

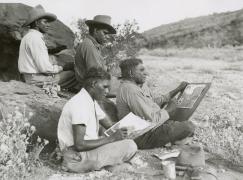

Battarbee returned in 1936, and Albert accompanied him on a two-month painting trip through the West McDonnell Ranges employed as a cameleer, cook and guide. Albert guided Battarbee through some of the most spectacular country in Central Australia, including Palm Valley, the James Ranges and Gosses Gorge and in return received his long-awaited lessons. It was on this trip that he learnt the basic techniques of watercolour and impressed Battarbee with his evident talent. These earliest works were signed simply ‘Albert’.

In the following few years, Albrecht and Battarbee arranged several exhibitions of Albert’s work. It was at this time that Albert chose his father’s traditional name and began signing his work ‘Albert Namatjira’. His first major public exhibition was opened in Melbourne on 5 December 1938. All 41 of his works sold within days. During World War II, Albert sold some of his paintings to Australian and American servicemen based in Alice Springs, although a shortage of paper around this time forced him to concentrate mainly on beautifully decorated wooden plaques.

Some early critics of his work claimed he was simply ‘copying the white man’, but in reality, he was painting with ‘country in mind’ and continually returned to sites imbued with his ancestral associations. The detailed patterning and high horizons – so characteristic of his work – blended Aboriginal and European modes of depiction.

Namatjira’s initiatives won national and international acclaim. As the first prominent Aboriginal artist to work in a modern idiom, he was widely regarded as a representative of assimilation. In 1944, he was included in Who’s Who in Australia. He was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953). In 1954, he was flown to Canberra to meet the Queen herself and in 1955 he was elected as an honorary member of the Royal Art Society of New South Wales. Then in 1957, he was granted Australian Citizenship. Despite all these accolades, Albert Namatjira endured racism and discrimination. The last years of his life were difficult as he himself came to understand the gulf that existed between his traditional Aboriginal world and the European world, he had set foot in through his art. Throughout all this, he remained a quiet and dignified man.

Albert Namatjira died on 8 August 1959, from a heart condition complicated by pneumonia. He is buried at the Memorial Cemetery, Memorial Drive Alice Springs. In 1994, led by his granddaughter Elaine, members of the Hermannsburg Potters. https://hermannsburg.com.au/stories/hermannsburg-potters ) produced a terracotta mural headstone for his grave. His wife Rubina died in 1974 and is buried at Hermannsburg.

Namatjira’s importance in art history in Australia lies in his development of a distinctive Aboriginal school of Central Australian landscape painting executed in watercolour. He was the first Aboriginal artist to be commercially exhibited nationally and internationally. His work became widely acclaimed and a national symbol for Aboriginal achievement. Aboriginal artists from other Arrarnta families continue to paint in the watercolour tradition today.

Media